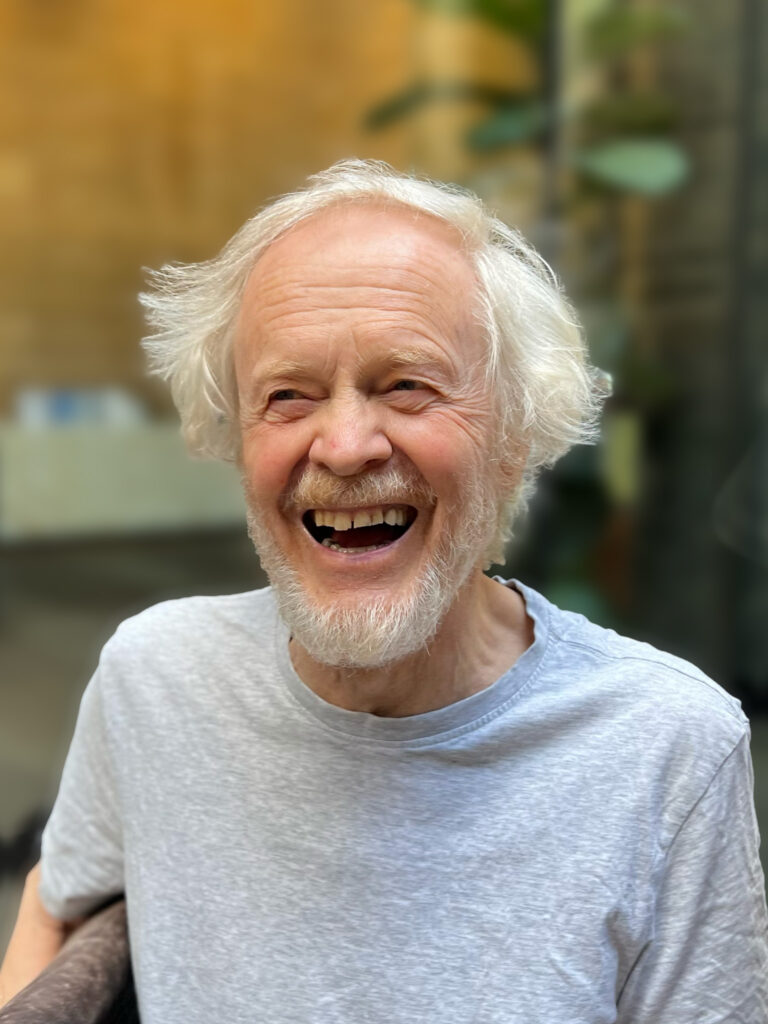

Lives amplified by tech aren’t always satisfying, says Phil Court. Especially if they’re not geared towards service and love…

We live in an age of technology that our ancestors would have regarded as either impossible or downright magical. After our brief honeymoon of delight in the perpetual “next generation” of tech-toys, we tend to take our newly acquired superpowers for granted. These days it’s easier to list what you can’t do with your hand-held device, than what it can do. Easier still, you can simply tell an artificial intelligence app to make the list for you. Or tell it to write you an essay on any topic you like.

But there’s a massive shadow side to our ever-increasing reliance on our devices. Australia has never had more widespread levels of mental illness. Those on the margins are falling through ever-widening cracks. Our ever-decreasing need for manual labour drives worsening health outcomes. And despite the virtual world of wall-to-wall social media, chat rooms and dating apps, a deep and despairing loneliness afflicts more of us than ever.

So what should we do about it? Let’s ask the artificial intelligence entity called Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3, or ChatGPT for short. Developed by the not-for-profit research and development company OpenAI, ChatGPT’s mission is “to ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all humanity.” Sounds promising! And noble too.

I asked Chat GPT to tell me what we need to live with purpose and flourish as persons. It instantly composed a 274-word reply that unfolded on my screen faster than I could read it. It finished with this:

“In summary, living with purpose and flourishing as a person requires identifying and aligning with one’s values and passions, building and maintaining positive relationships, taking care of one’s physical and mental health, and continually learning and growing. It’s important to approach these areas holistically and not just focus on one area alone.”

At first glance, ChatGPT’s advice seems to offer a balanced and reasonable formula. But if we scratch beneath the surface, it’s really just platitudes. It doesn’t distinguish between good and bad values, or healthy and unhealthy passions. It doesn’t tell me what makes a relationship “positive” rather than negative. In short, much like a horoscope, it’s the kind of advice we can make fit our own presuppositions, our own prejudices and our own priorities. One size fits all.

Author Andy Crouch suggests we look elsewhere for the answer. In his latest book, The Life We’re Looking For, Crouch takes us back to a Q&A session between Jesus and a bunch of his learned adversaries. In his gospel account of the life of Jesus, Mark records that “One of the scribes came up and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that Jesus answered them well, asked him, ‘Which commandment is the most important of all?’” (See Mark 12:28.) In other words, he’s asking Jesus, What is God’s purpose for us, and how should we live it out?

Here’s how Jesus replies:

“The most important command is, ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.”

Mark 12:29-31

The scribe agrees, and Mark tells us, “When Jesus saw that he answered wisely, he said to him, ‘You are not far from the kingdom of God.’ And after that no one dared to ask him any more questions.”

Jesus nailed it in one – well actually, in two. End of argument. He did it by pairing up two of the 613 commandments found in the Old Testament Law of Moses. For Jesus, they’re two sides of the same coin. Love the one who made you (Deuteronomy 6:4-5) and love the ones who, like you, he also made in his own image (Leviticus 19:18). And do all of it with all of your all. Give it everything you’ve got. Don’t leave anything in the locker room.

In these few words, Jesus identifies the four ingredients that together define our personhood; heart, soul, mind and strength. He challenges you to live out your love in each of these four aspects of yourself. In Crouch’s words, we are “heart-soul-mind-strength complexes designed for love.”

Here’s a summary of Crouch’s assessment of our personhood:

Heart: We are creatures “driven and drawn by desire. Our choices are shaped not just by thought but also emotion.”

Soul: “We have a depth of self that is uniquely ours, recognisably different from any other, a reality interior to us, and only partly available to others.”

Mind: We are “capable, far more than any other creature, of reflecting on the world, remembering and interpreting our experience, and analysing it.”

Strength: We are “capable of applying great energy toward work as well as play… Our bodies have obvious limits. But they are a marvel, especially when animated by heart, soul and mind.”

Crouch argues that “Of all the creatures on earth, we are by far the most dependent, the most relational, the most social, and the most capable of care. When we love, we are most fully and distinctively ourselves.” But the reality of our imperfect and self-centred natures means, “We discover very early in our lives that we are not at all what we were meant to be.”

The challenge we face is how we cope with our flaws, our disappointments and the slings and arrows that come our way. “The honest truth is that often, we just give in,” says Crouch. “We make choices that accelerate the patterns of emptiness and loneliness rather than reverse them. And thanks to a particularly tricky design feature of our heart-soul-mind-strength complex, it can initially seem that these small consolations and addictions offer us just enough of what we long for to get by. Human beings have made these kinds of choices ever since the pain of being persons was first felt. But today, we happen to have access to a way out of disappointment that offers more false comfort than our ancestors could ever have imagined.”

Crouch calls it “the superpower zone.” It’s the self-amplification that comes from the technological marvels that surround us, entice us, and all too often, enslave us. (Be honest: how many times have you checked in on your smart phone today? Too many to keep count?)

The problem is, amplifying ourselves with technology won’t cut it. Crouch characterises the great promise of technology as ‘We will no longer have to do X’ (wash our clothes by hand, build a huge fire every night to stay warm), and ‘We will now be able to do Y (move easily from town to town, or country to country by driving and flying). What we don’t give enough consideration to however is how those ‘promises’ are coupled with another set of imperatives, ‘We now won’t be able to do x (remember how to build a fire ….’) and, in fact ‘We now will be compelled to do y’ (put a smart phone in the hands of children in order for them to function in society.) There are times when this deal doesn’t serve us well. And relentlessly, we are diminished in heart, soul, mind and strength.

Despite his trenchant critique of the avalanche of “devices” for this, that and the other, Crouch is no luddite vainly trying to turn back time. He argues that technology can and should be developed and harnessed in ways that enhance our personhood, rather than diminish it. And that means being aware of all the aspects of our humanity – heart, soul, mind and strength.